1.4 Queen Christina of Sweden

1

David Beck

Portrait of Queen Christina of Sweden (1626-1689), dated 1650

Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, inv./cat.nr. NM 308

2

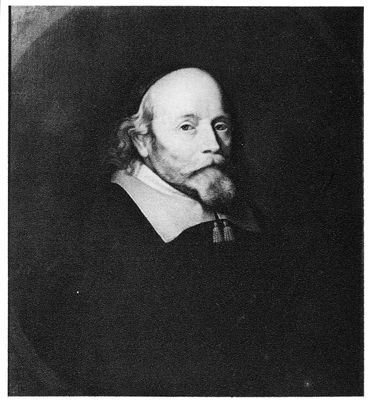

David Beck

Portrait of Axel Oxenstierna (1583-1654), c. 1650

Stockholm, Livrustkammaren

Queen Christina (1626-1689) took a keen interest in the arts and sciences. She attracted famous scholars to her court and corresponded assiduously with many others. Among the Dutchmen, it was Grotius and Vossius who occupied a place of privilege in Stockholm. Christina’s court painter was the Delft artist David Beck (1621-1656), who had become acceptable at court through his training with Van Dyck in London. Yet Beck did not relinquish his Dutch character so fully that he cannot be named with honor as an exponent of Dutch painting abroad. From 1647 on he was very active in Sweden. He painted portraits of the queen [1], Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna (1583-1654) [2] and many other personages who enjoyed the favor of the king at the time. In 1649 he also portrayed his compatriot, the great entrepreneur Louis de Geer (1587-1652) at Christina’s request (collection Gustaf de Geer [1859-1945], Malmö) [3].1 Beck held a trusted position at the court. The queen repeatedly sent him abroad to buy works of art and to paint portraits of friendly potentates. His sitters included the Danish royal couple [4-5] and the Duke of Holstein.2

3

David Beck

Portrait of Louis de Geer (1587-1652), dated 1650

Malmö, private collection Gustaf de (friherre) Geer

4

David Beck

Portrait of King Frederick III of Denmark (1609–1670), probably made in 1652

Leiden, Universitaire Bibliotheken Leiden, inv./cat.nr. AW 1208

5

David Beck

Portrait of Sophie Amalie of Brunswick-Lüneburg (1628-1685), probably made in 1652

Leiden, Universitaire Bibliotheken Leiden, inv./cat.nr. AW 1209

6

Abraham Wuchters

Portrait of Queen Christina of Sweden (1626-1689), 1660-1661

Uppsala (province), Skoklosters slott, inv./cat.nr. 615

7

Abraham Wuchters

Portrait of Queen Christina of Sweden (1626-1689), 1660-1661

Uppsala, Uppsala universitets konstsamlingar, inv./cat.nr. 381

In 1652 and 1653 Beck was in Holland. On this occasion he gave his father very valuable pictures and jewelry for safekeeping. Perhaps Beck, as ‘Kamerlingh ende schilder van de Koninghinne van Sweden’ (chamberlain and painter of the Queen of Sweden), had been sent ahead with part of the royal collection? In the same year, 1653, we encounter him in Rome, where he must again have served his queen, who was about to abdicate. He also visited Paris with her in 1656. While there he requested leave and died the same year in The Hague.3

After the death of Karl X Gustav in 1660, the queen returned to Stockholm, perhaps in the hope of once again becoming head of state. She looked around for a new court painter and found him in Abraham Wuchters (1608-1682), whom she detached from the Danish court for some time.4 But both the ex-queen and the painter were disappointed in their expectations, although the latter got to paint a whole series of distinguished people. His portraits of the queen belong to the most successful and characterful images of this exceptional woman (Skokloster, Uppsala) [6-7]. The Queen-Regent Hedwig Eleonora, Karl X Gustav and General Wrangel also approved of Wuchters [8-10].5 However, he needed to compete with the esteemed portraitist David Klöcker Ehrenstrahl (1628-1698) and therefore returned to Denmark a few years later.6

8

attributed to Abraham Wuchters

Portrait of Queen Hedwig Eleonora of Sweden (1636-1689), with a servant, c. 1660

Mariefred, Gripsholm Slott

9

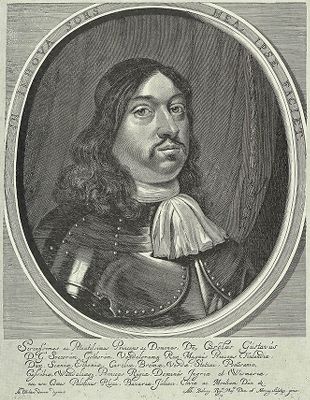

Albert Haelwegh after Abraham Wuchters

Portrait of King Karl X Gustav of Sweden (1622-1660), 1658

Copenhagen, SMK - The Royal Collection of Graphic Art

10

Abraham Wuchters

Portrait of Count Carl Gustaf Wrangel (1613-1676), c. 1658-1662

Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, inv./cat.nr. NMGrh 1228

Naturally a ruler as well-educated as Queen Christina had artistic ambitions beyond having herself portrayed by Dutch realists. While her court painter Beck was living in the Dutch Republic in 1652 and 1653 she had Sébastien Bourdon (1616-1671) come from Paris [11].7 Christina called the English miniature painter Alexander Cooper (1609-1660) to Stockholm at about the same time, because, as Houbraken says, he was ‘taken for the best portrait painter [in water colours]’.8

In 1641 a Swede, Georg Waldau (1626-1674) was sent to Holland for training. He studied with Joachim von Sandrart (1606-1688) and Jacques Jordaens (1593-1678).9 A Dutch student of Bourdon, Theodoor van der Schuer (1634-1707), joined Christina’s royal suite in Rome and loyally served her until 1665.10 If one wishes to assess her taste in art, one has to cast a glance at her valuable collection. The foundation was the Rudolfinian treasure chamber, which was captured in Prague in 1648. Over the years the queen had her agents buy many Italian and French pictures. She took the beautiful collection with her to Rome, where she left it to Cardinal Dezio Azzolini (1623-1689). After all sorts of inheritances and sales the pictures were acquired by the Duke of Orléans in 1715 and then sold to England during the French Revolution.11 However, the queen had left most of her Dutch and German pictures in Sweden. There were in any case not many. The portraits painted by Beck went with her to Italy, as did some pictures by Herman Saftleven, Cornelis van Poelenburch, Gerard van Honthorst and additional Dutch genre pieces and still lifes by unidentified artists.12 Christina’s buyers in Holland were the Swedish envoy Pieter Spiering van Silvercroon (1595-1652) [12] and his successor Harald Appelboom (1612-1674).13 Spiering Silfvercrona was a son of the tapestry weaver François Spiering (c. 1550-1630), who had also supplied Sweden and Denmark with his products. Silfvercrona (Silvercroon) greatly admired the art of Gerard Dou (1613-1675). He had himself and his family portrayed by Dou and did not skimp on the remuneration. He paid the exquisite Leiden painter ‘voor yder Konststukje zoo veel gelt, als het tegens zilver geleik wegen mogt’ (in translation: ‘for every piece of art as much money as its weight in silver’) [13-15].14 Her royal highness did not at all share this predilection of her envoy. She sent back all ten pictures that Spiering had assembled for her, because they did not please her.15 Nor is a portrait of Johannes Torrentius (1588-1644), which Michiel le Blon (1587-1658), painter and agent in Swedish service, had offered to Spiering as a great treasure in 1635, to be traced to Christina’s collection.16 As Spiering later settled in Stockholm, it is not unlikely that his picture collection also went to Sweden.17

11

Sébastien Bourdon

Portrait of Queen Christina of Sweden (1626-1689), c. 1652-1653

Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv./cat.nr. RF 767

12

possibly Gerard Dou or possibly Alexander Cooper

Portrait of Pieter Spiering van Silvercroon (c. 1595-1652), c. 1640-1645

Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, inv./cat.nr. NMB 38

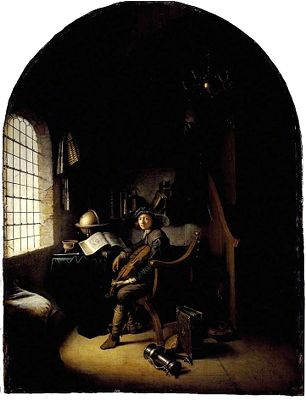

13

Gerard Dou

Young violinist sitting in his study room, dated 1637

Edinburgh (city, Scotland), National Galleries Scotland, inv./cat.nr. NG 2420

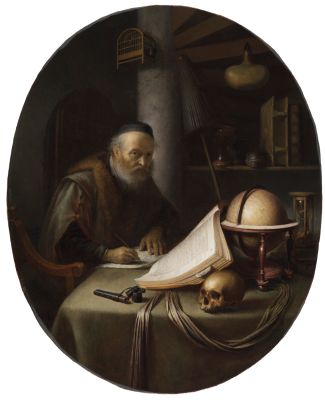

14

Gerard Dou

Scholar interrupted at his writing, c. 1635

New York City, The Leiden Collection, inv./cat.nr. GD-102

15

Gerard Dou

Old woman peeling apples in an interior, c. 1630-1634

Berlin (city, Germany), Gemäldegalerie (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin), inv./cat.nr. 2031

Notes

1 [Van Leeuwen/Roding 2024] The painting mentioned by Gerson is recorded as being dated 1650; another good version (RKDimages 107724), is in the collection of a member of the De Geer family in the Netherlands and is dated in the same way. The engraving by Jeremias Falck (RKDimages 107828), however, is dated 1649, suggesting that the above mentioned are both repetitions..

2 [Van Leeuwen/Roding 2024] The inventory of Beck’s estate after his death on 19 December 1656 lists a blue velvet book in quarto containing six drawings, including one of the king and queen of Denmark and one of ‘den hertogh van Hollsteyn (Bredius 1915-1921, vol. 4 (1917), p. 1272, under no. 2). The drawing of the king and queen of Denmark can be identified with the two drawings in the University Library in Leiden. A related engraving of Frederik III by Jeremias Falck is wrongly recorded in the British Museum as after Pieter Isaacsz (who died in 1625); instead it is probably after David Beck. The painting is now lost, but it must have been known to Ottomar Elliger, who repeated the work in a cartouche of flowers and fruit (RKDimages 113404).

3 [Gerson 1942/1983] Granberg 1886B; Alting Mees 1913; Poelmans 1917 and Poelmans 1929; Bredius 1915-1921, vol. 4 (1917), p. 1269-1281; Granberg 1918.

4 [Van Leeuwen/Roding 2024] For Wuchters' period in Sweden and its impact on his later career: Bøgh Rasmussen 2015, p. 5.4.

5 [Van Leeuwen/Roding 2024] Only copies or uncertain attributions of portraits of the Swedish King and Queen are known; the life-size originals seem to be lost (Bøgh Rasmussen 2015, p. 5.4).

6 [Gerson 1942/1983] Many images in Strömbom/Uggla 1927; Granberg 1911-1913, vol. 1 (1911), no. 529; Steneberg 1928; Steneberg 1940.

7 [Gerson 1942/1983] Compare also Steneberg 1935.

8 [Van Leeuwen/Roding 2024] Houbraken 1718-1721, vol. 2 (1719), p. 87 (as: Joan Couper); Horn/Van Leeuwen 2021, vol. 2, p. 87.

9 [Van Leeuwen/Roding 2024] Christina wanted to send Waldau – with the help of Michiel le Blon (1587-1658) – to Jacob Jordaens in Antwerp, as he was considered too young to go to Italy; however, the war thwarted these plans and Le Blon thought it better to leave him in the Dutch Republic or send him to his former master Sandrart in Germany (Granberg 1895, p. 76-86; Roosval et al. 1952-1967, vol. 5 [1967], p. 545-555).

10 [Van Leeuwen/Roding 2024] The mention of Van der Schuer as being commisioned by Queen Christina in Rome stems from Van Gool (Van Gool 1750-1751, vol. 1, p. 44-45). Actually, he went to Stockholm as the assistant of Sebastian Bourdon (Thuillier 2000, p. 67). In Rome, he resided in the Discesa di San Giuseppe in 1661 and 1662 where he shared lodgings with the engraver Cornelis Bloemaert (Hoogewerff 1942, p. 250-251; Bartoni 2012, p. 361). It is unclear whether Van der Schuer was still in Rome between 1663 (no longer recorded as living in the Discesa di San Giuseppe) and the Spring of 1665.

11 [Gerson 1942/1983] Granberg 1897; Granberg 1929-1932, vol. 1 (1929), p. 156, 182; Lugt 1936, p. 130.

12 [Gerson 1942/1983] Denucé 1932, p. 178-179, 191; Granberg 1929-1932, vol. 1 (1929), p. 138.

13 [Van Leeuwen/Roding 2024] On Spiering as an art agent: Noldus 2004, p. 102-104 (as: Peter Spierinck) and Veldman 2015-2016.

14 [Gerson 1942/1983] Houbraken 1718-1721, vol. 2 (1719), p. 4. [Van Leeuwen/Roding 2024] Horn/Van Leeuwen 2021, vol. 2, p. 4.

15 [Van Leeuwen/Roding 2024] For the 11 (not 10) paintings which were returned, presumably all works by Dou, see Granberg 1895, p. 12-15, 'Gerard Dous förnämsta arbeten - pä Stockholms slott'. In his catalogue of the queen’s collection, including the 1652 inventory, Granberg proposed several identifications (Granberg 1897, p. XXV-XLX, nos. 1-9 and 73-74). Another painting, representing Loth and his daughters (by Dou?), which also had come from Spiering, was not returned (Granberg 1897, no. 104). Also still in Stockholm is Gerard Dou’s Penitent Magdalen, which was delivered to Queen Christina by Michel le Blon (Granberg 1897, p. XXXVII, no. 56; Cavalli-Björkman/Fryklund/Sidén 2005, p. 162-163, no. 168, ill.). The assumption that the paintings by Dou were returned because Queen Christina did not like them is repeated in most literature. A more important reason for the restitution was probably that no payment had been made and that Spiering's stepson, Johan Philip Silvercroon van Blommert (c. 1625-1702), will have demanded the paintings back after Pieter Spiering's death in February 1652. It is known that Johan Philip − even years later − made efforts to still receive payment for other art objects his stepfather had provided. Compare Veldman 2015-2016, p. 248.

16 [Van Leeuwen/Roding 2024] See Noldus 2005, p. 97-102, esp. p. 99 and note 466. According to Veldman this story is incorrect and based on a misreading of a letter Le Blon wrote to Oxenstierna (Veldman 2015-2016, p. 237 and note 57).

17 [Gerson 1942/1983] On Spiering: Martin 1901, p. 42ff; Sandrart/Peltzer 1675/1925, p. 383, note 48; Frederiks 1888, p. 119; Wrangel 1901, p. 43, 101. [Van Leeuwen/Roding 2024] Spiering's stepson was both located in Sweden and in the Dutch Republic; he and his family kept living in Vijversteyn House in Rijswijk near the Hague, where Joachim van Sandrart visited him in 1667 (Veldman 2015-2016, p. 248,